A Discourse On Ethics

Sayyid Muhammad Husayn Tabataba'i

Al-Mizan, Vol. 2, Under Commentary of Surat ul-Baqarah: Verses 153 - 157

*********

Ethics is the science which looks into human traits, related to man's vegetable, animal and human characteristics, and differentiates the good traits from the bad ones, in order that man may complete his practical happiness by acquiring the good traits; and thus emanate from him such actions as attract to him general praise from the human society.

Ethics shows that human morality finally belongs to three comprehensive faculties of man. These faculties lead the psyche to acquire practical knowledge, from which emanate all actions of the human species.

These are the desire, anger and rational faculty. Human actions are divided into three categories: Either they are intended to gain some benefit, for example: eating, drinking and wearing clothes, etc.

They issue forth from the faculty of desire; or they are aimed at protecting, or repulsing harmful effects from, one's person, honour or property, etc. These actions emanate from the faculty of anger. Or they are related to mental conception and proposition, for example, arranging syllogism, preparation of argument, etc.

Such mental activities are caused by rational faculty. Man's personality is composed of these three faculties, and they, by joining together, emerge as a composite unit and become the source of all human activities and actions. In this way, man attains his felicity and happiness, which is the final cause of this composition.

It is therefore necessary for man not to let any of these three faculties deviate from the middle path to either the right or the left, not to allow any of these to exceed the limit or to be deficient - as it would disturb the ratio of that particular ingredient, which would result in changing the entire nature of the composite unit, that is, man himself. This would negate the reason for which the man was created, that is, the felicity of the whole species.

The middle course for any of the faculties is to use it as it should be - both in quantity and quality. The middle course for the faculty of desire is called continence, and its two sides of excess and deficiency are greed and undue quiescence, respectively.

The middle course for the faculty of anger is bravery, and the two sides are rashness and cowardice. The middle course of the faculty of rationality is called wisdom, and the two sides are deception and dull-mindedness.

When the three good characteristics - continence, bravery and wisdom - combine in a man, a fourth characteristic is born, just as a new quality emerges when different ingredients of a medicine or mixture are blended together. And that quality is called justice. Justice gives each faculty its due right and puts it in its proper place.

Its two undesirable sides are inflicting injustice and surrendering to it.

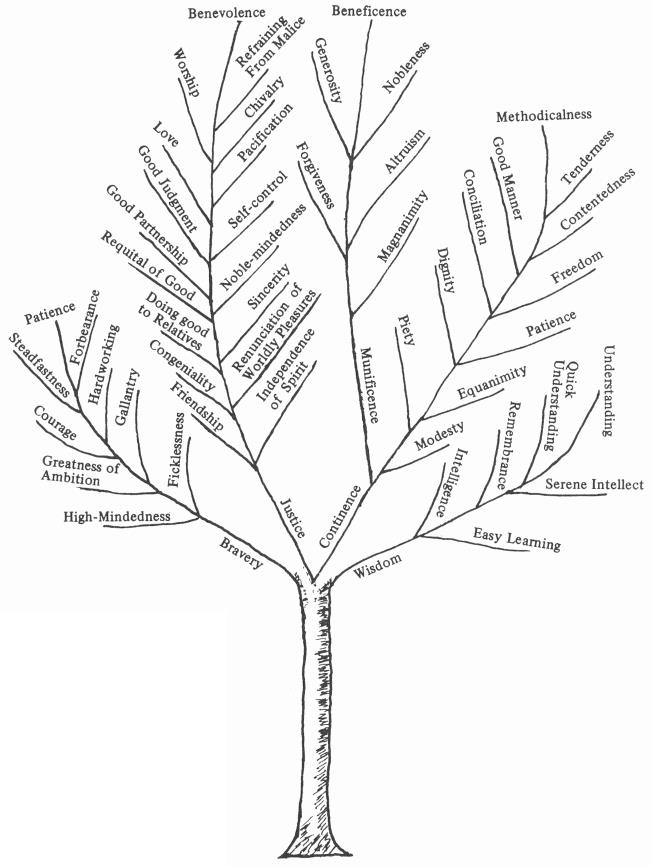

These four - continence, bravery, wisdom and justice - are the roots of all virtuous characteristics, of good morality. Each of them has numerous branches which issue forth from it and belong to it. They have the same relationship with the above-mentioned roots as a species has with its genus.

Examples of these branches are generosity and magnanimity, contentedness and gratitude, patience and gallantry, courage and modesty, sense of honour and sincerity, nobility and humility, and so on. These are the branches of virtuous characteristics, which are given in detail in the books of the Ethics. The following is a 'family-tree' showing its roots and branches1.

And the Ethics defines each of them and distinguishes the middle course from its two sides of excess and deficiency; then it explains why a virtue is virtue, then shows how it can be acquired, until it becomes a firm trait, that is, by firm belief that it is good and virtuous trait and by repeatedly practising it until it becomes a firmly-rooted characteristic of the soul.

For example: We say to a coward: Cowardice is born when the psyche is gripped by fear; and fear emanates from something which may happen or may not happen - in future; and such a thing, whose existence and inexistence both are equally possible, cannot be tipped to either side without a cause; a man of reason should not indulge in such fantasies; therefore, a man should not allow himself to be gripped by fear.

When a man teaches himself this theoretical aspect, and then repeatedly enters into dangerous situations and resolutely proceeds towards alarming perils, he soon gets rid of the bad trait of fear. The same is the case with all the virtues and evils.

The above description is based on the first system, as was explained in the Commentary. That system tries to reform the character and to create a balance, a moderation, in moral traits, in order that the man may be praised and his virtues lauded by the society.

Somewhat similar is the approach of the second system brought by the prophets and the divine legislators. The only difference is in the aims and objects of the two systems.

While the first system aims at acquiring a perfect trait because it is approved by the society and attracts praise from the people, the second one aims at achieving by it the genuine happiness for the man, that is, perfection of belief in Allah and His signs, and the felicity of the next world, which is the real happiness and perfection. Yet, both systems are similar in that, the ultimate goal of both is the perfection of man in his character and morals.

As for the third system (which was explained earlier), it differs from the above two, in that it aims at seeking the pleasure of Allah, not at achieving human perfection. Consequently, its goals sometimes differ from that of the earlier two systems. It is quite possible that what appears as the middle way from this point of view, may not look so from the other two angles.

When the faith of a servant proceeds on this path of perfection, when it goes on from strength to strength, his soul is attracted towards meditation about his Lord; he keeps the beautiful Divine Names before his vision, and constantly looks at His lovely attributes which are free from every defect and deficiency; his soul is relentlessly attracted to Allah going higher and higher in his meditation, until there comes a stage where he worships Allah as though he (man) were looking at Allah, and Allah were looking towards him. At this stage he feels the Divine Presence in his attraction, meditation and love.

The love increases from strength to strength, because man by nature loves beauty. Allah has said:

and those who believe are stronger in (their) love for Allah (2:165).

Such a man begins following the Messenger of Allah in all his doings, in every situation, because love of a thing results in the love of its signs, and the Messenger of Allah (S) is the wonderful sign of Allah. (In fact, the whole universe is a sign and token of Allah.)

This love becomes stronger and stronger until a time comes when the servant cuts himself from everything, in devotion of Allah; he loves nothing except his Lord, he bows before none other than Allah. Whenever such a man looks at a thing which has some beauty and attraction, he finds in it a sample - although imperfect - of the Divine Beauty.

He knows that it is but a reflection of the inexhaustible perfection, the unending beauty and incomprehensible splendour of Allah. Allah's is the beauty, grace, perfection and magnificence; every beauty and perfection found in other things, in reality belongs to Him, because everything is a sign of Allah - it is its only reality, it is nothing more than that; it has no other disposition; it is but a reflection showing the image of the original.

This man is, and remains, overwhelmed by love; and he does not look at anything but only because it is a sign of his Lord. In short, all strings connecting his heart to other things are snipped off, leaving it attached only to the love of Allah. Whatever he loves, it is only for the sake of Allah and in the cause of Allah.

At this stage, the mode of his perceptions and actions under-goes a drastic change. When he looks at a thing, he sees Allah before it and with it, everything loses its independence and identity in his eyes. What he sees and perceives is different from what other people see and perceive; the people look at things from be-hind a curtain, while he sees them in their true form.

This shows the difference in perception, and similar is the case of actions. As he does not love anything except Allah, he does not want any-thing except for Allah, seeking His Sublime Majesty.

He neither seeks nor intends, neither hopes no fears, neither chooses nor abandons, becomes neither despaired nor depressed, is neither pleased nor displeased - except for Allah and in the cause of Allah. Thus, his aims and goals differ totally from those of other people; his motive is diametrically opposed to that of his fellow beings.

Previously, he acquired a virtue because it was a human perfection, and discarded an evil because it was a defect. But now his only interest is in seeking the Sublime Majesty of Allah; he does not care about any perfection or defect, nor is he attracted to any worldly praise or cherished remembrance; he rises above this world as well as the next; he takes into consideration neither the Paradise nor the Hell - he discards everything and rises above them. Now, his destination is his Lord; his provision, his humility of servitude; and his guide, his love. As a poet has said:

Love narrated to me the traditions of amour,

Through its chain of narrators, from neighbourhood

of a distinguished personality,

And narrated to me the breath of fresh breeze,

From the branching trees, from the valley of euphorbia

from the heights of Najd,

From the tear, from my sour eye, from passion,

From sorrow, from my wounded heart, from ecstasy of love,

That my ardor and love have sworn together,

To my destruction till I am laid down in my grave.

This discourse, although short and concise, explains our theme (if you study it carefully). It shows that in this third system of the Ethics the question of human perfection or defect becomes irrelevant; and the aim is changed from human perfection to the Sublime Majesty of Allah.

As a result, the outlook is changed from those of the other two systems; and it may happen sometimes that what is counted as a virtue in other systems becomes evil in this one, and vice versa.

Now, we should turn our attention to one remaining topic. There is another theory of Ethics which differs from the above-mentioned three systems; and probably it may be counted as a separate system.

They say: Ethics and morality changes in its roots and shoots with the changes occurring in the society, because virtue and vice change with the changing society, they are not based on any permanent, unalterable, firm foundation. Allegedly it emanates from the theory of evolution of matter.

They say: Human society has come into being because of various needs and requirements of life, which man wants to fulfil through the agency of society. He tries to keep the society alive which, he thinks, preserves his own existence. The nature is governed by the law of evolution and gradual perfection.

Consequently, society too undergoes constant changes and proceeds to a more perfect and more developed goal. If an action conforms with the aim of society - that is, perfection - it is called virtue; otherwise, it is vice.

Therefore, virtue and vice cannot remain unchanged, they are not static or permanent. There is nothing like absolute virtue or absolute vice; they are relative ideas, which change with the changing societies, according to regions and times.

As the virtue and vice - being relative factors - under-go changes, so do the ethical and moral values. In other words, Ethics is not absolute; its views on good and bad characteristics are liable to change with circumstances.

From the above, we may infer that Ethics follows the nation-al or social aspirations - the aspirations which are a means of achieving the social perfection (which is the goal of the society); and virtue and vice are governed by it.

Whatever promotes development, whatever helps the society in reaching its goal and achieving its aspiration, is good and virtue; and whatever hinders from that goal, whatever keeps the society backward, is evil and vice.

Accordingly, lie, false allegation, indecency, hard-heartedness, robbery and shamelessness may become good and virtuous, if they promote the aspiration of the society. And truth, chastity and mercy may become bad and evil - if they hinder it from achieving its goal.

This is a gist of this strange theory which has been adopted by the materialist communists. This theory is not a new one, contrary to their claims. In ancient Greece, the Cynics reportedly had the same idea.

Likewise, Mazdakites (the followers of Mazdak, who lived in Iran during the reign of Kisra and was the first to call to communism) were practising it; and even today some primitive tribes in Africa and elsewhere follow this tenet.

However, it is a false theory, and the proof offered in its support is wrong both in its foundation and structure. Before exposing its falsehood, a few points should be made clear:

Every being - that which has external existence - has an inseparable personality of its own. Consequently, one being cannot be another being. For example, existence of Zayd has a personality and a sort of unity which prevents it from becoming the personality of 'Amr.

Zayd is one person and 'Amr is another; they are two persons, two human beings, not one. It is a premise whose truth cannot be doubted.

(There is a totally different proposition which says: “The physical universe is a being having one individual reality.” This proposition should not be confused with the above-mentioned premise.)

It follows that the external existence is one and the same with personality.' But mental ideas are different from external beings and their existence is not their personality. Reason admits that an idea - whatever it may be - may be applied to more than one individual, for example, the idea of man, or that of a tall man, or that of the man standing before us.

The logicians divide idea into general and particular. Also, they divide the particular into two categories of relative and real. But these divisions are done when an idea is seen vis-à-vis another idea, when it is put at the side of the other; or when it is seen in relation to external existence.

This property of the ideas - their applicability to more than one individual - is also sometimes called “generality”; its opposite being “individuality” or “unity”.

An external physical being is governed by the law of change and general movement. Therefore, it has an expanse and that expanse is divisible into boundaries and pieces, each piece being different from other preceding or following ones.

Yet, it is connected with them in its existence. Otherwise, without that connection, it could not be said to be changing or evolving. (If a thing is removed completely and is replaced by an entirely new thing, it cannot be said that the first evolved and changed into the second. If one thing is to change into another, there must be a common factor joining them together).

It follows that that movement is a single thing having its own identity and personality. It looks numerous when it is seen in relation to the boundaries of a thing (as mentioned above). That relation distinguishes one piece from the others. But as for the movement itself, it is a single uninterrupted flow.

This characteristic of the movement - this constant flow - is also called a ”generality” in contrast to the relations it has with each boundary; we say “general movement”, meaning a movement free of its relations with the boundaries and pieces.

This “generality” is a thing existing in reality, unlike the “generality of the ideas” mentioned in (2) above, which is mental attribute of idea - an imaginary attribute of an imaginary being.

Undoubtedly, man is a physical being; humanity has many members, as well as its own laws and characteristics. What is created by nature is one individual, singly and separately. It does not create the collection of people which we call human society. Of course, the nature was aware that man needs somethings to perfect his existence which he could not obtain on his own.

Therefore, the nature equipped him with organs, faculties and powers which would be useful in his endeavours to make up his deficiencies within the framework of society. Obviously, the single man is the goal of creation, primarily and principally, while society is a secondary goal, just a by-product.

The human nature demands a society and proceeds towards it, (if we can use the words of demand, causality and movement - in their real sense - about the society!). What is the real relation between man and this society?

An individual man is a single and personal being (in the sense we have described above). At the same time, he is constantly on move, changing, evolving, proceeding to his perfection.

That is why every piece of his changing being is different from other pieces. Yet his is a nature, flowing, “general”, preserved in all the stages of the changes; in short, his nature is a single personality.

This nature found in this individual man is preserved by the means of procreation, by branching out of one individual into other individuals. It is this factor which is called “nature of the species”.

It is preserved through the individuals, even if they are changed, even if they undergo creation and destruction (in the same way as was explained about the individual's nature). Individual's nature exists and proceeds towards personal perfection.

Likewise, nature of species exists and proceeds towards the perfection of the species. There is no doubt that this endeavour for perfection of species exists in the natural system.

That is what we mean when we say, for example, that the human species proceeds towards perfection; or that today's man is a more perfect being than the primitive man. The same demand for perfection of species is in the minds of those scientists who speak about the evolution of species.

Had there not been a nature of species, existing in reality, preserved in the individuals.(or in species), such talks would not have had any value - it would have been just a metaphorical speech. As with the individuals, so with the society.

There is an individual, or let us say particular, society, which is found amongst the people of a nation, of a time or of a region. Also, there is a general society found in the human species, continuing with its continuation, evolving with its evolution (if it be correct that society, like a social man, is an externally existing condition of an externally existing nature!).

Society moves and evolves with the movements and changes of man. This society is a single entity from the initial stage of the movement to wherever it proceeds to, with a general existence. This ”one” (which changes because of its relation with each and every boundary) becomes divided into numerous pieces. And every “piece” is a part of the society, that is, a “man”.

The parts or members of the society rely in their being on the persons of mankind. In the same way the general civilization - in the sense described above - depends on the general human nature. The law governing a unit is a unit of the law; and the law governing a ”general” is the general rule. (”General rule” does not mean an abstract rule, because we are not talking about ”general ideas”.)

Undoubtedly an individual man, being a single entity, is governed by a rule, which continues with his continuation. Yet that rule undergoes partial changes, following the changes occurring in the man himself. For example, there is the rule that the physical man takes food, acts by his will, has feelings and imagination, thinks and perceives.

These rules exist and continue as long as the man himself exists. Of course, minor changes may occur in those general rules consequent to the changes occurring in the man. The same principle applies to the humanity in general, the general mankind, which exists with the existence of its individuals.

As establishment of society is a law of human nature and one of its characteristics, so the general society is a characteristic of the general human species. (By general society we mean the society, per se, the society established by human nature and which is continuing uninterruptedly from the day man came into being to this time.)

This general society exists and continues with the humanity. And the laws of society which it has brought into being will remain intact as long as the general society exists. Of course, some minor changes may occur in it but the main principles will remain unchanged, like the mankind itself, which continues although its individual members go on changing.

Now it is clear that there are some ethical principles which are unchangeable and are valid for ever - like general virtue and vice - as the general society is firm, constant and unalterable from the beginning.

Society cannot turn into non-society (i.e., individuality) - although a particular civilization may give way to another particular civilization. Likewise, general virtue (and vice) cannot turn into non-virtue (or non-vice) - although a particular virtue may evolve into some other particular virtue.

An individual man needs - for his existence and continuation - some perfections and benefits which he must achieve and acquire for his own self. That is why nature has equipped him with organs and faculties to help him in this compulsory quest, for example, alimentary canal for food intake and digestion, and sexual organs for reproduction and continuation of the species. It is obligatory for man to use these systems for the purpose they have been created for.

He should not completely ignore them by leaving them unused, because it would be against the dictate of nature. Likewise, he should not over-indulge in these activities, he should not eat or cohabit more than necessary; for example, he should not go on eating until he becomes sick, or dies, or becomes unable to use his other faculties. He must keep to the middle course in achieving all his requirements, perfections and benefits.

This middle course is called continence; and its two undesirable sides are greed and undue quiescence. Likewise, we see that every individual, in his existence and continuation, is faced with many such things which are harmful to him and which he is obliged to resist, and repulse from him-self. And this “obligation” is proved by the fact that nature has equipped him with the organs and powers to defend himself with.

Therefore, it is obligatory for him to defend himself and resist the harmful things - keeping himself on the middle course. He should not neglect and crush these powers nor should he overuse them. This middle course is called bravery, and the other two sides are rashness and cowardice.

The same is the case with wisdom and its two sides, deception and dull-mindedness; as well as with justice and its two sides, injustice and surrender to injustice.

These are, thus, the four faculties and virtues which are demanded by the nature of an individual man - the nature which is equipped with its necessary tools: continence, bravery, wisdom and justice. And all of them are good and virtues. Good is that which is in conformity with the ultimate goal of a thing and promotes its perfection and felicity; and, as explained above, all the four are in conformity with the felicity of the individual. And their eight opposites are bad and evil.

When an individual, by his nature and in himself, has this attribute, then he would be having it also within the framework of the society. Society, being a product of nature, cannot negate nature's rules; otherwise, it would be a contradiction in terms. After all, what is society if not the co-operation of the individuals to facilitate the perfection of their natures and achievement of their aspirations.

Human species in framework of the “general” society has the same characteristics as an individual has in his particular society, as mentioned above.

Human species in its civilization tries to achieve its perfection by repulsing what is harmful and acquiring what is beneficial to it; by learning as much as is good for it and practising justice - that is, giving everyone his due right, without indulging into injustice and without surrendering to injustice.

And all these four characteristics are virtues. The civilization, per sé, decrees that they are absolute virtues and their opposites are absolute vices.

The above discourse clearly shows that in the constant and perpetual human society, there are absolute virtues and absolute vices - society cannot “be” without them. It also shows that the four fundamental ethical values are absolutely good and virtuous and their opposites absolutely bad and evils; as has been decreed by the social nature of humanity. And the case of their branches is not different from that of the roots.

They too are absolute and unchanging - although there may occur some differences sometimes in their applications, as we shall mention afterwards.

Now it is clear that what they have said concerning relativity in morality is not correct:

They said: “Absolute virtue and vice do not exist. What exists is the relative virtue and relative vice; and it is a changing thing which varies with regions, times and societies.”

Reply: It is a fallacy, because they have confused the “generality of idea” with “generality (i.e., continuation) of existence”. It is true that absolute good and vice - in the meaning of general ideas - do not have external (i.e., real) existence.

But here we are not concerned with them. What we are concerned with are absolute virtue and vice - in the meaning of lasting social factors which continue as long as the society exists, by decree of nature.

The aim of the society is the happiness of the species. And it is impossible to think that all happenings and possible events and actions would always be good for the society. Surely some would conform with its needs and some would not.

Accordingly there would always be good and evil in the society. How can we suppose existence of a society - of any type - in which the members do not believe that every one should be given his due right, or that it is necessary to gain benefit to its proper limit, or that they must protect and defend the cause of the society as and when needed, or that the knowledge - by which man differentiates what is beneficial from what is harmful - is a good attribute?

These four beliefs are the above-mentioned justice, continence, bravery and wisdom. As was said, every society, of any description whatsoever, decrees that these four characteristics are good and virtuous. Moreover, how can we think of a society that does not ordain that one must refrain from indecencies? And that feeling is modesty, a branch of continence.

Or a society that does not exhort one to be enraged when rights are usurped or the sanctity of sacred things violated? And it is the earnest sense of honour which is a branch of bravery. Or that one should be happy with his due social rights? And it is contentedness.

Or that one should preserve one's social status without snubbing other people, without putting them out of countenance by one's arrogance? And it is modesty and humility. We may go on enumerating in the same way each and every branch of the ethics and morality.

They say: “The views often differ from society to society on what virtue is. One thing is considered as virtue in one society, while another society treats it as vice.”

Reply: Of course, there are some minor examples of this phenomenon. But it is not because one society believed in acquiring good traits while the other dismissed it as unnecessary. Whatever the difference, it only occurs because one society believes that trait to be good, while the other thinks it is evil. So the difference is not about the principle, it is only in its application.

For example: The societies ruled by autocratic rulers used to believe that the sovereign had total authority over his subjects, and absolute power to do whatever he wished and order whatever he liked. But that belief was not based on any negative attitude towards justice.

It actually emanated from their belief that that absolute power was the due right of the ruler; they thought that what the ruler was doing was not injustice, he was only exercising his due authority and taking his just right.

Likewise, some societies thought that it was a shame if their kings studied to acquire knowledge, as is reported about French kings of the medieval ages. But it was not because they looked down at the virtue of knowledge; it was only because they thought that acquiring knowledge of politics and studying the ways of managing various government departments would conflict with the king's rightful royal activities and engagements.

In the same way, some societies do not acknowledge any excellence in chastity of women (i.e., not establishing sexual relation with any man other than their husbands), and their modesty. Nor do they believe that their men should feel enraged if their women indulged in licentiousness. The same is the case with some other virtues like contentedness and humbleness etc.

But it is only because those societies do not think that these things fall under continence, modesty, self-respect, contentedness and humbleness. It is not that they do not accept these main virtues as virtues. After all, they praise a judge or a ruler if he practices continence in his rule and judgment.

They appreciate it if one is ashamed of breaking a law; they laud a man who, overcome by national zeal, defends the nation's independence, the cause of civilization, or the sanctity of other sacred values. They praise a man who remains content with what the law has allotted to him; and applaud the loyalty and obedience shown by the public to their leaders and rulers.

They say: “Whether a characteristic is good depends on its conformity with the goals of social aspirations.” Then they come to the conclusion that the said characteristic's excellence depends on its conformity with the society's goals. But it is a clear fallacy. Society is an institution which comes into being when its members enforce, and act upon, all the laws decreed by nature.

This society is bound to take them to their happiness and felicity (provided there is no disturbance in its arrangement and flow); and the society is bound to have some rules and regulations like virtue and vice, good and evil. On the other hand “society's aspiration” is just a set of some imaginary ideas, invented for creating a society on prescribed lines by imposing it on its members.

In other words, society and society's aspirations are two completely different things: Society is an established fact, society's aspiration is only a potential which is yet to come into being; the former is an actual fact while the latter is only a plan yet to be implemented.

How could one be equated with the other? The virtue and vice are brought into being by the general society on the demands of the human nature; how could such an actual fact be brought under the domain of some aspirations - the aspirations which are nothing but some imaginary notions?

Question: The general civilization, brought into being by nature, has no authority of its own; whatever authority there is, it belongs to its goals and aspirations - especially if it is a theory conforming to the happiness of the society's individuals.

Reply: The preceding discussion about virtue and vice and good and evil, shall be repeated in this case again - until the talk stops at a permanent, perpetual and unchanging decree of nature.

Apart from that, there is another difficulty. Let us suppose that virtue and vice as well as all the rules of civilization depend on the goals and aspirations of the society. And it is those aspirations on which the arguments of these people are based.

But it is possible - nay a fact - that there may be different conflicting goals and aspirations within one society, or between different societies. Which aspiration would then prevail? Which one the people should give preference to?

Which would be acceptable to the general society? The fact is that in this situation there will only be one criterion, and that is the power and domination; in other words, might is right. How can it be believed that the human nature led the human beings to a social structure whose parts are in conflict with one another? Can the society be governed by a rule which would negate the society itself? Is it not an ignominious contradiction in the rule of nature and the demands of its existence?

A Few Traditions on some Related Topics

Imam al-Baqir (‘a) said: “A man came to the Messenger of Allah (S) and said: 'I am keen (and) enthusiastic for jihad.' (The Messenger of Allah) said: 'Then do jihad in the way of Allah, because if you are killed, you shall remain alive near Allah and sustained, if you die (before that), then your reward is indeed with Allah...'

The author says: The Prophet's words, “and if you die...”, point to the word of Allah:

and whoever goes forth from his house emigrating to Allah and His Messenger, and then death overtakes him, his reward is indeed with Allah... (4:100).

It also shows that proceeding to jihad is emigration to Allah and His Messenger.

Imam as-Sadiq (‘a) said about the prophet Isma'i1, whom Allah has named “Truthful in promise”: “He was named 'Truthful in promise' because he had promised a man (to wait for him) in a place.

So he remained waiting for that man for one year. There-fore, Allah named him 'True of promise'. Then that man came to him after that (long) time and Isma'il said to him, 'I have been waiting for you...' ” (al-Kafi )

The author says: It is a thing which average wisdom would probably say was a deviation from middle course, while Allah has counted it as an excellent virtue of the said prophet, increasing thereby his prestige and raising his status, as He has said:

And mention Isma'il in the Book, surely he was truthful in (his) promise, and he was a messenger, a prophet. (19:54).

And he enjoined on his family prayer and alms-giving, and was one in whom his Lord was well pleased (19:55).

The fact is that the criterion by which this action was judged is different from the one used by common wisdom. The average wisdom, the common sense, looks at the things according to its own views, and Allah looks after His friends by His Own help and support; and the word of Allah is the High. Many similar events have been narrated about the Prophet, the Imams and other friends of Allah.

Question: How can rules of the shari'ah go against the dictates of reason, in situations where reason may have a say?

Reply: True that reason may judge the virtue or vice of an action wherever it is possible for it to do so. But that thing or action should first come within its jurisdiction before it can pronounce its judgment on it.

And we have explained earlier that such actions (as described in the above tradition) are governed by the third system, and that system takes such actions out of the jurisdiction of human intellect and reason - reason does not have any say against or about them. It is the way of the Divine Knowledge.

Apparently the prophet Isma'il (‘a) had given that man unconditional promise by saying, 'I shall wait for you here until you come back to me.' Therefore, he stuck to that unconditional wording, to save himself from breaking the promise, and to fulfil what Allah had put in his mind and made his tongue utter.

Of the same import is an event related about the Prophet that he was near the Sacred Mosque when one of his companions told him that he would come back to him, and the Prophet promised to wait for him until he would return.

That man went away and did not return, and the Prophet remained there three days waiting for him in the same place which he had promised. That man passed by that place after three days and found the Prophet sitting there waiting for him and he himself had forgotten the promise.

As-Sayyid ar-Radi has narrated from the Leader of the faithfuls ('Ali - ‘a) that he heard someone saying: “Surely we are Allah's and to Him shall we surely return” (2:156) Thereupon, he ('Ali - ‘a) said: “O man! Verily our word, Surely we are Allah's, is acknowledgment by us that we belong to Him, and, to Him shall we surely return, is acknowledgment by us that we are to die.” (al-Khasa'is)

The author says: Its meaning is clear in the light of the earlier given explanation. The tradition has been narrated in detail in al-Kafi.

Ishaq ibn 'Ammar and 'Abdullah ibn Sinan have narrated from as-Sadiq (‘a) that he said: “The Messenger of Allah (S) has said: 'Allah, the Mighty, the Great, has said: “I have given the world as loan to My servants.

Then whoever gives Me a loan from it, I give him ten times to seven-hundred times in lieu of one. And whoever does not give Me a loan and I take something from him by force, then I give him three things that if I gave one of them to My angels they would be pleased of Me.” ' ” Then Abu 'Abdillah said: ”(It is) the words of Allah:

“Who, when a misfortune befalls them, say: 'Surely we are Allah's and to Him we shall surely return’” (2:156)

“Those are they on whom are blessings and mercy from their Lord, and those are the followers of the right course” (2:157).

Then Abu 'Abdillah (‘a) said: “It is for the man from whom Allah takes something forcibly.” (al-Kafi)

The author says: This tradition is narrated by other chains, all having nearly the same theme.

Imam as-Sadiq (‘a) said: “as-Salah ( اَلصَّلٰوةُ ) from Allah is mercy, and from the angels is purification, and from the people is prayer.” (Ma'ani ‘1-akhbar)

The author says: There are other traditions of the same meaning.

At first glance, there appears to be a conflict between this and the preceding tradition. This tradition explains as-salah as mercy, while the preceding one counts as-salah as other than mercy; and this view is further strengthened by the wording of the verse itself which mentions as-salah and mercy separately, “blessings and mercy from Allah”. But in fact there is no contradiction as we have explained in detail in the Commentary.

- 1. since the author has described the branches of virtuous characteristics in the text in tree form, and in the explanatory figure (of the original work) he has also chosen the tree form representation, we therefore have duplicated the explanatory figure in the same manner (pub.)