Mulla Sadra’s View Of God’s Relations To The Sensible And Imaginal Worlds: Imagination And The Variable Intensity Of Being

Hajj Muhammad Legenhausen

The Imam Khomeini Education and Research Institute, Qom, Iran

Abstract

In order to understand Mulla Sadra’s view of God’s relation to the sensible and imaginal worlds a series of problems are traced that have figured prominently in the development of Islamic philosophy. We begin with Plato’s divided line and the idea that the human faculties correspond to levels of reality. In Aristotle and Plotinus, the imagination is given a role superior to that found in Plato’s texts. The role of the imagination is given still greater prominence in Avicenna, who links it to intellectual cognition.

Sohravardi posits the existence of imaginal worlds to correspond to the faculty of the imagination. He also elaborates a complex hierarchy of sensory, imaginal, and intellectual lights and identifies God with the Light of lights. Elements in the hierarchy are distinguished by degrees of intensity of brightness and darkness. In Mulla Sadra’s philosophical system, Sohravardi’s hierarchy of lights is replaced by one of being and it is being itself that is said to differentiate itself by variations in intensity. Corresponding to the incorporeal imaginal worlds, Mulla Sadra argues that the faculty of imagination, and not just the intellect, is incorruptible. He uses this theory to explain divine rewards and punishments, the bodily resurrection, the purification of the soul, mystical visions, and the nature of revelation.

Mulla Sadra’s Philosophy of Existence

Ṣadr al-Dīn Shīrāzī (c. 1571-2—1635-6), popularly known as Mulla Sadra, elaborated a philosophy of existence over the course of his career that drew upon discussions found

in Peripatetic (mashā‘ī), Illuminationist (‘ishrāqī), theological (kalāmī), and mystical irfānī) schools of thought. The synthesis that resulted is not a fully homogenized system. The language of theoretical mysticism (irfān al-naẓarī) is not entirely brought into conformity with the language of Avicenna (who, together with his followers are known as peripatetics, because of their reliance on various Aristotelian teachings, although the Islamic Peripatetics employed neo-Platonist doctrines no less than Aristotelian ones); the Illuminationist concepts are not completely taken over, but revised in the new system; and teachings of Shi’i kalām are reinterpreted in ways that continue to provoke heated disputes among Shi’i philosophers and theologians today. Some theologians consider Mulla Sadra to have substituted philosophical for theological concepts; while there are Muslim philosophers who see him as introducing religious themes where the pursuit of philosophical argumentation is required. Nevertheless, there can be no doubt about the fact that one of the major sorts of Shi’i Islamic theology is that of writers who follow the main outlines of Mulla Sadra’s philosophy of existence, albeit with important reservations, qualifications, and revisions.

Introductions to the philosophy of Mulla Sadra explain that it flys with the two wings of the priority of existence over quiddity and the gradation (or modulation) of existence.11 These philosophical principles become theological doctrines when we appreciate that in Mulla Sadra’s system of thought, God is existence. This is the basic bridge between philosophy and theology in Mulla Sadra; and it is at least implicit in several of the Islamic schools of thought on which his work was based: clearly in some Sufi writings, and implicitly in Avicenna. Since the claim that God is existence provokes charges of pantheism, it is seldom stated so baldly. Qualifications are added: God is ultimate existence, pure or unadulterated existence, the reality (ḥaqīqat) of existence, or absolute existence. With the qualifications come allusions to lesser sorts of existence: existence that is proximate rather than ultimate, impure, and conditioned. The division of existence into pure and impure threatens the philosophical principles of the unity and simplicity of existence, and the corresponding theological doctrines of divine unity and simplicity. Mulla Sadra’s specific version of the gradation of existence is designed to realign it with these principles.

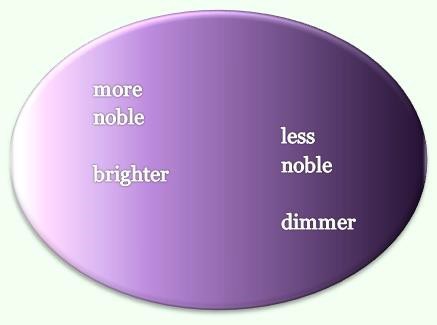

Platonic And Neoplatonic Gradations Of Being

The idea that there are grades of existence is a recurrent theme in the history of Western philosophy that is especially prominent and influential through Plato’s discussions in the Republic of the divided line. There, in a discussion of contradictions, which introduces the notion of mixed or impure being, in Book V of the Republic, Socrates gets Glaucon to agree that the things we call big, small, light, and heavy are also their opposites2. They conclude that such opinions are “somehow rolling around between what is not and what purely is.3” In the next Book, the sun is said to play a role in vision analogous to the role of the Form of the Good in knowledge. This is followed by a description of the divided line, which may be depicted as in the following diagram.

Table 1: Plato’s Divided Line

The divided line correlates cognitive faculties with their appropriate objects. Here we should take notice of five points: (1) there is a correlation between faculties of cognition and levels of existence; (2) there is mixed as well as pure being; (3); there is intellectual illumination compared to the light of the sun; (4) the purest kinds of being are immaterial; and (5) there is a path toward perfection from the lower to the higher reaches of the realms compared in the divided line. These five points are retained in Neo-Platonic works and subsequent Christian and Islamic writings, although there are many other points at which later writers diverge far from the Platonic model, and over which they differ in ways that set them far apart from one another.

From the very start, there is a displacement of the role of imagination. Plato’s faculty of eikasia is never mentioned by Aristotle. He uses another Platonic term, phantasia, for the ability to form and retain images. Plato had introduced the term phantasia in the Theatetus and the Sophist to refer to appearances, especially the sort that could explain perceptual errors, such as the misidentification of someone seen from afar4. Aristotle, on the other hand, uses the term in a more general sense for the ability of the soul to produce images, regardless whether they are veridical or not. Aristotle ranks the faculty of imagination higher than that of sensation, and claims that only the higher animals possess imagination5. The Aristotelian discussion of imagination lays the groundwork for the revision of Plato’s divided line that eliminates eikasia and inserts phantasia between sensory perception and dianoia6.

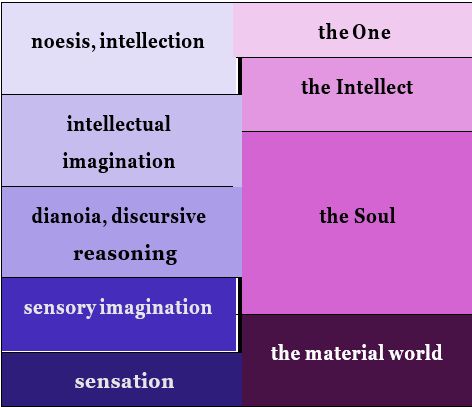

This revision, along with a multitude of further embellishments to the hierarchy of being, was carried out by the Neo-Platonists. For Plato, images are imperfect copies of bodies, and therefore rank lower than them. For Plotinus, however, images, such as those seen in a mirror, retain elements of the form of the bodies they depict without their matter. Since the immaterial is more subtle than the material, it should be placed higher in the cosmological hierarchy. The revision in the conception of imagination carried out by Plotinus is not limited to its repositioning in this hierarchy; he also argues that the imagination is the foundation of memory, and that it provides not only images first associated with sense perception, but also “images” derived from the higher faculties of reason. So, there is a doubling of the imagination as what appears is taken from the sensible or the intelligible worlds. We have both a sensible imagination, and, in the fourth Ennead, an intellectual imagination7. The Neoplatonist hierarchies of being and of the faculties might then be depicted roughly as follows.

Table 2: The Plotinian Hierarchy

The One, the Intellect, and the Soul and called hypostases. The Intellect is described as a shadow of the One and as what emanates from it. Likewise, the Intellect emanates the Soul, and the material world is a shadow of the soul. The sensory imagination is the foundation for memory and the images it provides might be seen as straddling the realms of the Soul and the material world. The intellectual imagination also has one foot in the Soul and one in the Intellect.

These themes of gradations or levels of being that correspond to cognitive faculties in which the imagination plays a pivotal role in connecting the world of the intellect with the sensible world are developed with numerous variations in Christian and Islamic traditions of thought8.

Shaykh al-Ra’is, Shaykh al-Ishraq and Sadral- Muta’allihin

The honorary titles by which Avicenna (d. 1037) and Sohravardi (d. 1191) are known are: Shaykh al-Ra‘īs (the premier shaykh) and Shaykh al-Ishrāq (the shaykh of illumination), respectively. Both developed their own plan of the levels of being, and in both, there is an association between divisions of the cognitive faculties and division of things known by them. In both, the imagination plays an important role as a bridge between the different levels of the cosmos and the psyche, although the ways in which they viewed the cosmological and psychological orders were very different. Both provide important elements for the synthesis and further development of these themes found in the works of Mulla Sadra, whose honorific is Ṣadr al-Muta„āllihīn, the Foremost of the Transcendentalists.

Avicenna provides us with a cosmology that is neo-Platonic in is emmanationism, Aristotelian in its rejection of the Platonic Forms, and Ptolomaic in its astronomy. Aristotelian psychology is as much a part of Avicennan philosophy as the theory of emanation and the Ptolomaic celestial spheres, for Avicenna is no less indebted to the discussions and commentaries about the topics of Aristotle’s book On the Soul, known in Arabic as Kitāb al-Nafs, than he was to the neo-Platonic texts that were circulating in Arabic at his time.

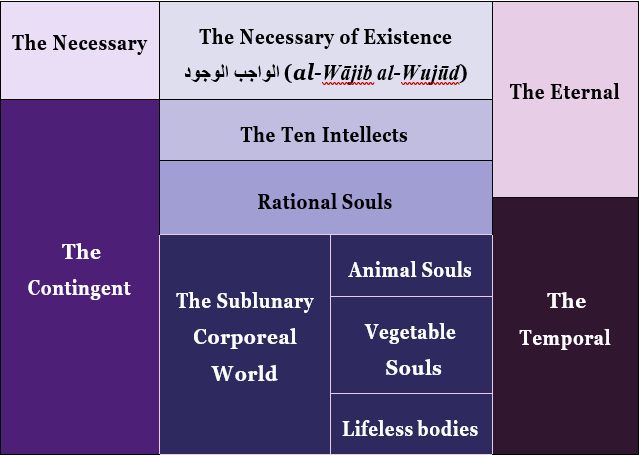

The cosmology that Avicenna presents is not the three hypostases of Plotinus: the One, the Intellect, and the Soul; but rather the Necessary in its existence (wājib al- wujūd), then ten intellects, each associated with a celestial sphere, and finally the sublunary realm of generation and corruption9.

Table 3: Avicenna's Divisions of Being

The rational soul is temporal, insofar as it is originated in time (ḥudūth) with the body; but it is eternal, for it is a separate substance from the body and continues to exist with the corruption of the body. The link between the rational soul and the body is found in the middle portion of the brain, not in Descartes’ pineal gland, but in the active imagination which becomes the cognitive faculty when impressed with forms from the intellect.

In religious terms, the Necessary is God and the intellects are angels. So, we can divide existence into the necessary and the contingent, where the contingent includes the angels and the world of generation and corruption. We can also divide the world between the unchanging and the temporal, with God and the angels unchanging, but the sublunary world changing. (The motions of the stars and planets are considered to be of a different genus from the motions of earthly objects.) Another division is between external existence (or singular existence) and mental existence. Forms existing in the intellects, in rational souls, and in animal souls have mental existence, where mental existence is grounded in the external existence of the soul or intellect in which these forms are mentally instantiated10. What is most striking in Avicenna’s view of the cosmos is the way he describes the human soul as standing between the unchanging and temporal realms, facing upward with its theoretical reason and downward with its practical reason, for theoretical reason is concerned with abstract universal truths while practical reason is concerned with particular actions.11

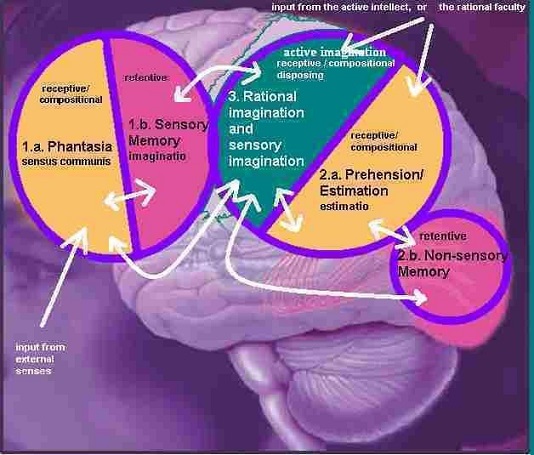

As mentioned above, Avicenna held that although the rational soul comes into existence with the body, it does not perish with the body, and it must be considered to be a separable substance distinct from the body, rather than an Aristotelian entelechy. He also introduced the idea that in addition to the five external senses of corporeal perception, there are also five inner senses, physiological powers with locations in the brain. If we consider memory as a kind of imagination, all of the inner senses are divisions of imagination. There is some confusion in the terminology used12, but in sum Avicenna divides the inner senses into two pairs, each pair consisting of a receptive/compositional member and a retentive member13. The first pair, located in the anterior part of the brain, (1.a) receives data from the exterior senses, composes images from them, and (1.b) stores them. The second pair (2.a) composes non-sensory ideas or images about things (the standard example is that the wolf is frightening in the psyche of the sheep) and (2.b) stores these images. Finally, located in the middle of the brain is

a faculty of active imagination, which is limited to sensory images in animals, but in humans can also become rational imagination, corresponding to the Greek dianoia. What I am calling active imagination here is not so designated by Avicenna. His commentator, Naṣīr al-Dīn Ṭūsī (d. 1274), called it the “disposing” (mutaṣarifah) imagination, in the sense that it actively takes elements from other parts of the imagination, the senses, or the intellect, which are then at its disposal to be composed in new ways14.

Table 4: Avicenna's Brain

Avicenna explained that in animals, it is the mutakhayilah (yet another term for imagination, here with the meaning of sensory image composition), but in humans, it is the faculty of thinking, mufakkirah. According to the insightful analysis of Deborah Black, discursive human reasoning does not take place in the intellect alone, but occurs through both the faculty of reason and the imagination15. This makes the imagination a true bridge between the divine and temporal realms of existence.

Although Avicenna’s metaphysics is dualistic, it is not a Cartesian dualism because mental existence is physical, located in the brain, and will perish with the brain, in contrast with the eternal existence of the intellects. The soul that is subject to divine rewards and punishments is not some combination of inner senses. It is only the human rational soul or intellect that is eternal, and the descriptions of divine rewards and punishments described in religious texts are to be understood figuratively, as appeals to the human imagination that can motivate people to turn away from material and worldly pleasures and to seek the intellectual pleasures of understanding, that is, of conjunction with the active intellect, by means of which one approaches God. Avicenna also developed a theory of prophetic revelation based on conjunction with the active intellect, identified with the angel Gabriel. In many of his writings on theological issues, such as religious language, the immortality of the soul, eschatology, revelation, and mysticism, the role of the imagination is pivotal, as it is through cogitation that a human being turns from the worldly to the divine realms and becomes the recipient of divine grace.

The fundamental structure of Avicenna’s division of the stages of being and his philosophical psychology dominated discussions among Muslims, Christians, and Jews in the centuries that followed. In his earliest philosophical writings, more than one hundred fifty years after Avicenna, Sohravardi followed him with very little divergence. In some of his mature thought, however, he suggested several radical innovations.

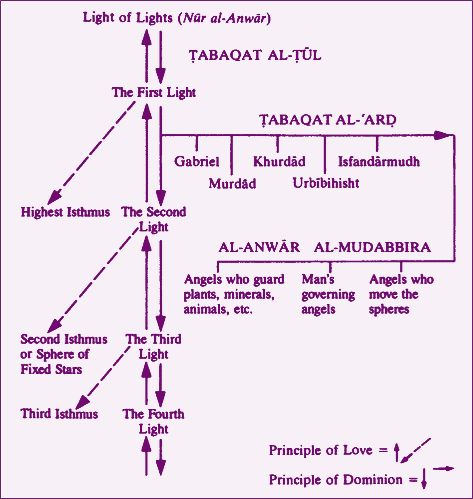

Sohravardi (also Suhrawardī) was an Iranian philosopher and mystic who was probably killed when he was about thirty-seven years old in Aleppo at the order of Saladin because of political intrigues in Syria16. His major work is Ḥikmat al-‘Ishrāq (The Philosophy of Illumination). He uses the term illumination to refer to intellectual as well as sensible lights, where light is defined as that which is self-manifesting. He objected to Avicenna’s divisions of being and to his distinction between existence and essence because Sohravardi thought that existence is just an abstract concept, not what is known through direct experience. Nevertheless, Sohravardi’s cosmology remains comparable to Avicenna’s, in that it begins with God at the top, who creates the next level by emanation, the level of intellects or angels, and the levels of emanation end with the material world. God, however, is described as the Light of lights (Nūr al-Anwār) rather than the Necessary of existence (Wājib al-Wujūd), and the angelic realm is not limited to the ten intellects of Avicenna, but consists of three major tiers of intellects or angels:

(1) the longitudinal order of angelic lights, which includes lights governing the celestial spheres as in Avicenna’s cosmology;

(2) the latitudinal order of angelic lights, which emanates from the longitudinal order, and in which one finds Zoroastrian angels and Platonic forms which are not related to one another through emanation; and

(3) the order of regent lights, which are like guardian angels that direct the movements of the celestial spheres.

The number of these lights is finite but very large17. Ian Richard Netton provides a most helpful glimpse at Sohravardi’s cosmology with the following diagram:18

Table 5: Sohravardi's Lights

Netton’s diagram only shows the top section of Sohravardi’s complex cosmological hierarchy. What is not shown here, but is most important for our discussion, is that between the angelic and corporeal worlds, Sohravardi inserts another realm, the world of the imagination ‘ālam al-khiyāl) or world of archetypes (‘ālam al-mithāl), sometimes called the “land of nowhere” (nākojāābād), which Henry Corbin would later dub the mundus imaginalis19. Sohravardi was led to posit this imaginal world on the basis of reflections about phenomena of light, such as its apparently instantaneous disappearance when its source is extinguished and the enormous expanse of reflections in small mirrors, which suggested to him that sensible light was incorporeal, although not as sublime as the ranks of the intellectual lights shown in the diagram, since it is seen, and can take shapes and have colors. So, what we consider to be physical light is not corporeal, and in addition to sensible lights, there are psychic lights and non- sensible intellectual lights of various ranks.

The assumption of an imaginal world whose existence is independent of the human (and animal) faculties through which it may be perceived enabled a restoration of correspondence between the major faculties of sensory perception, imagination, and intellection and worlds of objects perceived through these faculties. For Sohravardi, the imaginal world is not an imaginary world, but a real world populated by mirror images and mental images, such as what is seen in visions and mystical intuitions, with which Sohravardi seems to have had both first-hand experience and testimonial knowledge through his association with various Sufis.

Sohravardi’s style of philosophizing is daring and innovative (for example, in his rejection of the dominant peripatetic hylomorphism, and in his employment of themes from ancient Iranian traditions), while at the same time attentive to the dialectics of argumentation and logical form. These features are quite obvious in his discussion of the cognitive faculties and the imagination. The concern he displays for questions of logic, however, are no obstacle to a preoccupation with esoteric topics and the composition of allegories.

In The Philosophy of Illumination, Sohravardi rejects the enumeration of Avicenna’s five inner senses20 (although he adheres to this in other writings21), and he denies that there are receptive and retentive faculties that accept and retain forms that are impressed on them22. He gives several arguments to show that it is not reasonable to think that sensible forms are literally impressed on something in the brain. He concludes that the brain must be able to receive and retain sensible forms in some other manner than the mechanics of impression. Avicenna had omitted a storehouse of memory for cognition because he explained intellectual memory as the habituation of the cognitive faculty to have concourse with the intellectual world.

In effect, Sohravardi suggests that the same sort of analysis could be applied to the imagination. There is no need to store images in memory if the operations of memory can be explained as the habituation of the soul’s managing light to direct concourse with the imaginal world, although he admits that there may be a special faculty of memory for this purpose23. He also denies that there is any significant difference between prehension (wahm, estimatio) and the active imagination, since both engage in the composition and arrangement of forms present to the soul24. When perceptions occur, regardless whether they are intellectual, imaginal, or sensory, instead of impressions of the forms in the sense organs or in the brain, the barriers are removed between the knower and the known that enable illumination to take place. All perception and knowing is illuminative and occurs through the direct presence of the perceived to the perceiver25. The imaginal world is densely populated. It contains everything from the sensory appearances of angels in revelation to the figures seen in mirrors. The path of the mystic requires learning to navigate through this jungle of forms, and ultimately to leave it behind in order to reach the path upward to the Light of Lights through the angelic orders, and for this purpose Sohravardi recommends various spiritual exercises26.

One further aspect of the illuminationist theory requires our attention and returns us to the task we set out to perform: tashkīk, continuous gradation or the capacity for attenuation and intensification. While legions of philosophers have defended some version of what Arthur Lovejoy called the great chain of being,27 they have found various degrees of continuity along the chain. For Sohravardi, the continuity is (partially) observable and explained by his theory of lights, the philosophy of illumination.

Some minerals, like coral, closely approach the station of animals. Some animals, such as the ape, approach the condition of man in the perfection of their inner faculties and in other respects. In general, the lowest ranks of the higher degree are close to the lower degree, while the highest ranks of the lower degree of all existents nearly approach the higher degree. Some of the human managing lights are nearly intellect, while the lower of them are nearly like those of the beasts28.

Shortly after these and similar remarks about the proximities of different ranks of lights he asserts the principle of differentiation in simplicity which is the hallmark of tashkīk, variation in intensity:

You should not imagine that the incorporeal lights… have magnitude…. Rather, these are simple lights in which there is no composition in any respect. All share in the luminous reality, as you know. They differ only in perfection and deficiency. Deficiency in the luminous reality ends in that which is not self-subsistent but is only a state in another.29

The topic of difference by intensity or tashkīk is briefly mentioned by name in Avicenna’s metaphysics of The Healing. Avicenna discusses several forms of ranking by priority, and he claims that the concept of such rankings is one in which there is an analogous relationship, a relation of tashkīk, such that the things related in such an order are almost combined into one. In such orderings, what is prior in rank has properties that are lacking in the posterior. For example, if positions a and b are ranked by distance from a starting point, o, so that a is prior to b, then a will have a nearness to o that is lacked by b, while the nearness b has to o will be exceeded by a. This kind of relation can be applied to various orderings. Most importantly, if a is cause of b where a and b are simultaneous and a is both necessary and sufficient for b, the necessary concurrence of a and b does not prevent us from recognizing a priority in a that is lacking in b.30

Sohravardi criticizes Avicenna’s analysis of differences in intensity because for Avicenna all such differences are found in the relations that two objects have to a third, and it is differences in these relations that explain priority and posteriority, that is, in a category of accidents. For Sohravardi, on the other hand, Avicenna has failed to realize that intensity and diminution can occur in the essence of a thing and not just in its accidents.

The individual instances of heat are not distinguished by a differentia, for the answer to the question, “What is it?” does not change; nor do they differ by an accident. They differ by a third category: perfection and deficiency…. The theory of the Peripatetics about what is more or less intense is arbitrary; for according to them, one animal cannot be more intense in its animality than another. However, they define animal as “a body with a soul, sensible and moving at will.” That animal whose soul is more able to cause motion and whose senses are keener certainly has more perfect sensation and movement. The fact that common usage does not allow one to say that this animal is more perfectly animal than that one does not imply that it is not so31.

Avicenna allows for variation in gradation to occur in accidents, while Sohravardi holds that this sort of variation or tashkīk occurs both in accidents and in quiddities (whatnesses, such as natural kinds, species and genera); but they both agree that there can be no difference in the intensity of being32. This claim is one of the original doctrines of Mulla Sadra’s transcendent wisdom, ḥikmat al-muta„ālliyah.

Mulla Sadra on the Variable Intensity of Being

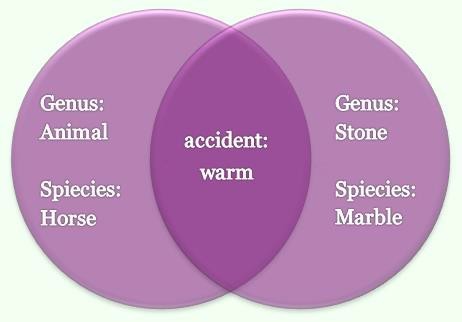

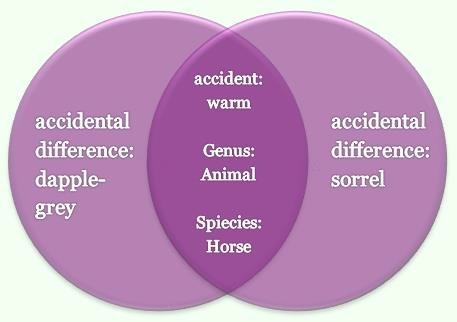

Mulla Sadra accepts the four part categorization of distinctions introduced by Sohravardi. If we consider two things both of which fall under some universal concept, the difference between them must be one of the following:

The universal that unites them is an accidental property, but they differ with regard to their entire quiddities (such as a particular horse and a piece of marble in the sunshine, both of which are warm).

Figure 1

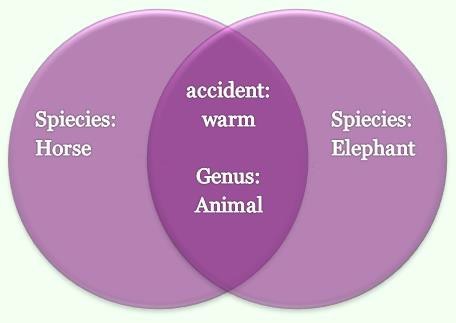

The universal that unites them is their genus, but they differ with regard to their specific differences (such as a horse and an elephant).

Figure 2

The universal that unites them is their species or kind, but they differ with regard to some accident not necessary for the quiddity, a non-essential property, (such as two horses).

Figure 3

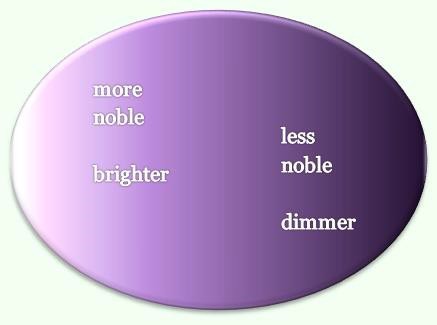

They differ with regard to perfection and imperfection (as two lights)33.

Figure 4

It is the fourth kind of difference to which Mulla Sadra applies a detailed study in which he defends the idea that there can be differences in perfection or intensity in being. Two entities can differ in such a manner that the difference between them is not due to differences in the application of a concept, e.g., through the use of ambiguous or analogical predication, so that the difference between two things to which the concept F applies is to be explained by a distinction in the meaning of F as applied to the more perfect thing and another meaning appropriate to the less perfect thing.

Furthermore, the difference is not to be explained as due to different relations to some other thing, such as a starting point or a paradigm. Instead, Mulla Sadra holds, the very same thing that unites the two things, the respect in which they are one (being existent), can also be what distinguishes them, the respect in which they are not one (the being existent of the two differ). Existence can both unite things under the single concept of existence and also distinguish things that have different intensities of existence. There is, thus, multiplicity in unity and unity in multiplicity. This claim was ignored by Mulla Sadra’s own immediate followers, and was later considered by some to be simply outlandish. It remains quite controversial today34.

In the peripatetic view, if two white things differ in the intensity of their whiteness, such as snow and ivory, this does not mean that whiteness itself has degrees of intensity, but only that the application of the univocal term “white” is true of both things while they differ in some other accident of their color, so that ivory is a bit yellowish in addition to being white. Because of the additional accident, the ivory is said to be less perfectly white than the snow. At least this is how some of the defenders of the peripatetic perspective in Islamic philosophy sought to answer their illuminationist critics: variation in intensity is in the application of an accident to an entity, without there being any variation in the intensity of any particular accident35. Although the peripatetics offered various analyses, they all agreed that the fourth kind of distinction mentioned above generally reduces to the third. Differences in intensity do not constitute a special kind of distinction; they are merely accidental differences.

For the illuminationists, on the other hand, the application of a single predicate, such as “white” to snow and ivory must be grounded in the essences of the snow and ivory rather than merely what is attributed to these essences. The concept of white qua concept does not admit differences in degree, for it is not the concept that becomes more or less intense with the purity of the whiteness of the object; rather, the objects to which the concept is applied differ in the degree of their whitenesses, and this can only be explained by the fact that the white objects themselves, that is, their essences (essence = dhāt), differ in intensity with respect to being white. The things to which attributions are made admit to different degrees; so, the variability in intensity is to be found in quiddities or substances.

Mulla Sadra accepted the illuminationist arguments for the fourth kind of distinction, a kind of difference in intensity that cannot be reduced to the presence or absence of discrete accidents. He also agreed with Sohravardi that the source of the distinction had to be found in differences in degree or intensity in some respect within the objects so distinguished. Distinctions by analogical predication must reflect analogical distinctions in ontology if they are not arbitrary projections. However, while Sohravardi traced such distinctions at the ontological level to differences in the intensities of quiddities or substances, Mulla Sadra held that the grounding had to go deeper, that it resided in differences in the intensities of the existences of the distinct entities, for the ultimate substratum of predication is not a quiddity or a substance, but the existence that is placed in the category of substance and is said to have some particular quiddity.

Once this step was taken (the replacement of Sohravardi’s fundamentality of quiddity by the fundamentality of existence), and this replacement was applied to the question of distinctions in intensity, the next question Mulla Sadra raised was whether all distinctions could not ultimately be reduced to distinctions in the intensity of existence. If so, then all multiplicity could be explained in a manner compatible with the Sufis’ insistence that in the entire world there was no more than a single reality, the reality of God. The mystics’ view had been criticized as leading to a kind of pantheism in which every finite thing is identical to God or to an acosmism in which the existence of the world and finite objects is denied. Tashkīk al-wujūd, the variable intensity of existence, would offer another alternative: there is only one reality, but this reality has multiplicity in its unity and unity in its multiplicity.

In order to connect all distinct entities by relations of variation in intensity, it was proposed that the gradation of existence could be horizontal as well as vertical. Vertical variation in intensity (tashkīk-e ṭūlī) occurs between two entities when one is emanated from the other. Horizontal variation in intensity (tashkīk-e ‘araḍī) occurs between a and b when both are emanated from a higher level of being. Everything that exists is united in the individuality of all existence; and at the same time, since existence includes variable intensity, it is existence that differentiates all distinct entities.

In this way, what began as a question of the analysis of universals whose instances could be ranked according to priority evolved into a question of philosophical mysticism36.

Mulla Sadra on the Imagination

In discussions of ḥikmat al-muta ‘ālliyah, imagination is divided between the separate or detached imagination (khiyāl al-munfaṣil) and the attached imagination (khiyāl al-muttaṣil). Mulla Sadra accepts the imaginal worlds of Sohravari, which are called the detached imagination, and denies Avicenna’s theory of impressions stored in the brain; but he gives a much more complex analysis. First, he holds that there are internal imaginal worlds as well as external ones. The images in the mind that result from Satanic temptations cannot have emanated from the world of intellects, contrary to the images of true visions. Hence, Mulla Sadra consigns the false images to the internal world of imagination, which is dependent on the activity of the soul, particularly on the faculty of the active imagination, and emanates from the soul; and he reserves the detached imaginal worlds for the images and ideas that are true reflections of the higher worlds of intellect from which they emanate. Second, he denies Sohravardi’s idea that such things as the images in mirrors and rainbows exist in an imaginal world.

Such images are merely like shadows of corporeal entities and have a subsidiary existence because of their dependence on bodies. Third, he holds that genies are corporeal, but that they have subtle bodies, while Sohravardi also placed such entities in the imaginal world37. In sum, Mulla Sadra divides the mundis imaginalis into two parts: a lower imaginal world that is completely dependent on the activity of the soul, and a higher detached imaginal world that is emanated from the intellects.

The division in the imaginal worlds requires that the faculties of imagination have a more active role to play for Mulla Sadra than for Ibn Sina or Sohravardi, for the imagination creates the world of images within the mind as well as perceiving the images of the detached imaginal world through the habituation of its concourse with them. All of the images, whether in the lower or higher imaginal worlds, are incorporeal. Since perception is explained as a kind of unification between the knower and the known, the faculty that perceives the imaginal and intellectual forms must, like them, be incorporeal. So, while Ibn Sina and Sohravardi held that with the corruption of the body the inner senses and outer senses are all corrupted and nothing remains of the soul but the eternal rational faculty, Mulla Sadra held that the faculty of imagination was no less incorruptible than the human intellect. Just as we can have visual perception in dreams without the use of the visual senses, we can have imaginal experiences after death, without the use of the corruptible aspects of the internal senses38.

When the soul departs the body, according to Mulla Sadra, the imagination is freed from the confines of the body, and is thereby made stronger, to such an extent that it becomes capable of creating or emanating a detached imaginal world; it is with reference to this creation of the disembodied faculty of imagination that Mulla Sadra explains the rewards and punishments of the afterlife and the bodily resurrection of the dead. Furthermore, when the soul departs the body, it is said to leave a “strange tail” part of which remains with the body and which may experience the terrors of the grave. This is a part of the imagination that perceives corporeal forms39.

If we review the course of the development of Islamic philosophy, we find that Avicenna rejects the Aristotelian definition of the soul as the first entelechy and instead argues that it is a separable substance. The human intellect is able to have concourse with an immaterial and independently existing world of intellects; but the inner senses are corporeal and are corrupted with the corruption of the body. Nevertheless, the active imagination serves as the cognitive faculty that links the embodied soul to the world of intellects. With Sohravardi, the imaginal world is added to the world of intellects as immaterial and independently existing. The inner senses remain corporal and mortal, but the imagination is able to bring the soul into position to perceive the imaginal world. Finally, with Mulla Sadra, the faculty of imagination is added to the faculty of the intellect as immaterial and immortal; and this faculty plays an essential role in explaining the relations between God and man through revelation, the Resurrection, and the afterlife40.

According to Mulla Sadra, a proper understanding of the relations between God and man requires an appropriate philosophical psychology. On the other hand, he admits that the nature of the imaginal worlds cannot be determined by philosophical argument alone, and one must have recourse to divine revelation and the narrations of the infallibles41; and he faults Avicenna and the peripatetics for having failed to appreciate the mysteries of the comprehensive unity of the soul, despite its multiplicity of faculties, a unity that he explains on the basis of his principle of the variable intensity of being, tashkīk al-wujūd.

Just as the world consists of different levels: divine, intellectual, psychic, and corporeal; so, too, the human being, the microcosm, is corporeal, psychic, and intellectual42. These levels of human existence appear successively through the substantial motion of the soul, which is corporeal in its origination but spiritual in its subsequent survival and persistence43. According to the principle of the variable intensity of being, the more intense levels include the subordinate levels:

The soul in reality… has existential degrees in order from the noble to the more noble, and for this there is movement in the perfecting of substance. Whenever it arrives at a level of the perfection of substance, it encompasses more and completely includes the previous levels…. Likewise, the nature of man, I mean his essence and soul, is the completion of everything that precedes him in kind: animal, vegetable, and mineral. The complete thing is the thing with what is additional to it. So the human, in reality, is all of these kinds of things, and his form is the form of all of them44.

The appearance of the different levels in man occurs gradually with the intensification of the being of an individual. This substantial motion of the individual human being is made possible by the varying degrees of intensity in being, tashkīk al- wujūd. Thus, Mulla Sadra criticizes Avicenna for holding that the eternal soul enters the fetus in the fourth month as an immaterial intellect.

Rather, at the beginning it is an actual imagination, and a potential intellect. Then gradually due to the repetition of perceptions, the abstraction of intelligibles from the sensibles, and universals from the particulars, it emerges from the level of potential intellect to the level of actual intellect. So its essence transmutes and transfers in this substantial transformation from the imaginative faculty to the intellective faculty45.

For Mulla Sadra, the power of the imagination, which he also calls “the psychic man” (insān nafsānī), is the intermediary between the corporeal man and the man of intellect. The imagination is also the faculty by which man enters the next world with the death of the body:

…what remains is the imaginal power (of the soul), which is a substance essentially separate from the body. This imaginal power is the last of the first (physical) modality of being, and the beginning of the other world’s modality of being46.

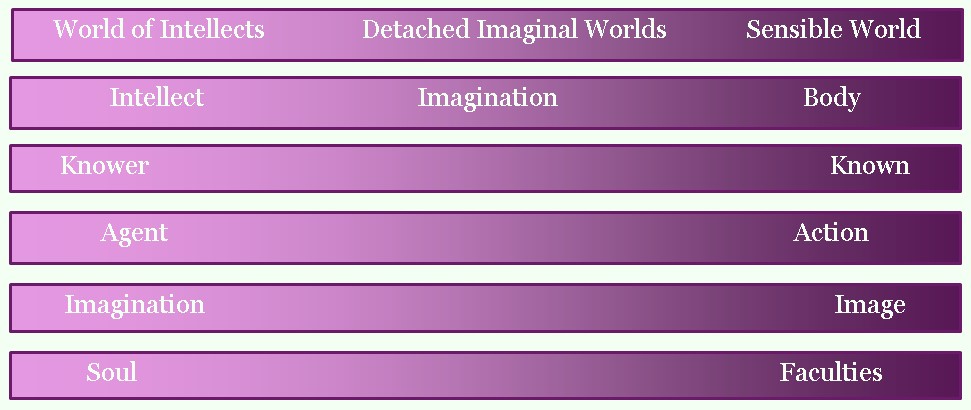

The relation between the soul and the imaginal forms it perceives is also a relation of unity in difference or graduated intensity of being, for the being of the image is united with the being of the imagination, but is a dilution of the strength of the soul’s being. Hence each person has direct personal experience of the gradation of being, of unity in difference and difference in unity, because of (1) the experience of one’s images and acts of will in relation to one’s self (the unity in difference of the knower and the known, the agent and the acts of agency); (2) the experience of the emergence from corporeal to psychic and then to intellectual capacities; and (3) the experience of the unity in difference of the soul with its multiple faculties; not to mention (4) the experience of death and the postmortem persistence of imagination. Hence, the role of the imagination as intermediary reaches an unprecedented summit in the work of Mulla Sadra that is made possible through his doctrine of the gradation of being. In each of these cases there is a single existence relative to which one is the emanating cause of the being of the other, and in each of these, the imagination makes the graduated nature of this existence manifest.

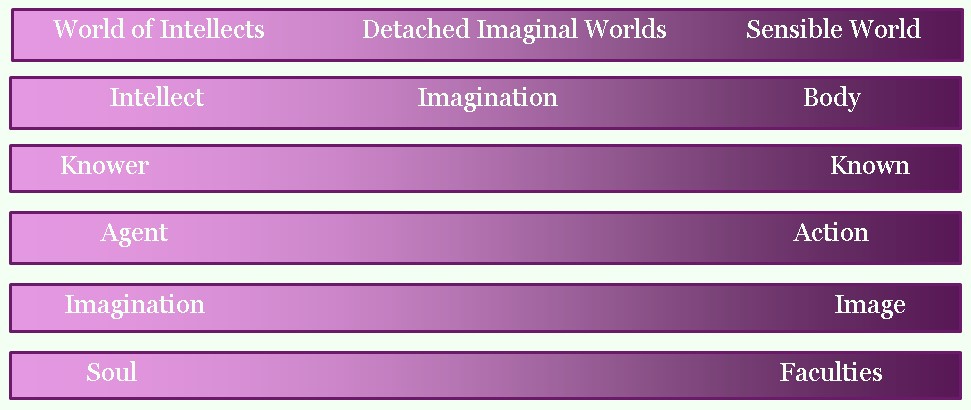

Figure 5: Examples of attenuation of existence

In each of these cases the items on the left and right share a single existence that is differentiated, according to Mulla Sadra, by differences in the intensity of being, whereby the item on the left emanates the item on the left.

Mulla Sadra on God’s Relations to the Sensible and Imaginal Worlds

According to Sohravardi, the causal relations that bind the different levels of existence from the Light of lights to the dark corporeal world are indications of a grounding relation between quiddities that differ in intensity. The quiddity of the cause is of a greater intensity than the quiddity of the effect. Mulla Sadra accepts the idea that the causal relation of complete dependence is one of priority in intensity (i.e., it is tashkīkī), but he rejects Sohravardi’s view of existence as a mere abstraction and its displacement in favor of light, defined as that which is essentially self-manifesting. Mulla Sadra observes, “existence is precisely the same as self-manifestation.”47 and, thus, reinstates existence for divinity and views causal dependence as a relation between levels of existence that differ in intensity, with the cause of greater intensity than its effects. However, Sohravardi’s analysis of bodies was entirely negative: Bodies are barriers to light that come about because of the shadows that lights cast. Hence, there is a dualism in Sohravardi’s metaphysics between light and shadow, the immaterial and the material.

For Mulla Sadra, on the other hand, the existence of each level includes the existence of its effect. Each level of emanation is a shadow of the level from which it is emanated, and all the levels consist of nothing but existence. Mulla Sadra also explains this by saying that the effect of a complete cause is nothing but the relation itself (‘ayn al-rabṭ) of the cause to this effect; and the union between cause and effect is is called the ‘union of the real with the diluted’ (ittiḥād ḥaqīqah wa raqīqah)48.

As Ayatullah Javadi Amuli frequently explains, according to Mulla Sadra, God hangs down the rope of existence for us:

So, we have these two arcs: sometimes from above to below, and sometimes from below to above. If there is no path, neither descent nor ascent is possible. If concepts, expressions, or quiddities were fundamental, there would be no path. If existence were fundamental but discrete, there would also be no path. However, existence is fundamental, and it is gradual and has degrees. We are constantly going up and down in this inner elevator.

What has reality in the world is being, and being is a gradual reality (ḥaqīqat) that is continuous and ordered by dependence. It is not cut, dispersed or scattered. The grace of this being, in religious terms, is that God has told us that He has sent down this religion and way just as a rope is sent down. He has hung down the rope; He has not thrown it down…. one end of it is in God’s hand and one end of it is in our hands. Between us and God there is this way…. Since existence is fundamental and reality is a matter of degree, there is a rope that God has hung down, not thrown down. If so, the sending down of grace from above to below is made possible, and also going from below to above by the grace of God is also possible. Likewise, what Mulla Sadra said was according the abilities of his students in that age. Otherwise, he should have said that man is corporeal in origin, spiritual in survival, intellectual in survival, and higher and higher… until it is no longer permitted49.

The two arcs mentioned by Ayatullah Javadi are the arcs of descent and ascent discussed by Sufi writers in the school of Ibn al-‘Arabi50. The arc of descent is also described as a pyramid of levels of emanation; while the arc of ascent is the path taken by the wayfarer toward God. In order to achieve felicity, one should gain knowledge to the extent of one’s ability of the stages along these two arcs.

And he [one who seeks felicity] should know the order of the system from origin to the return; and that existence is ordered from the First, the Exalted, to the intellect, and from it to the souls, and from them to the natures until it ends at the materials and bodies. Then it is ordered from them upwardly to minieral, then to vegetable, then to animal, then forward to the level of the acquired intellect; and then, finally, it returns to that from which it began51.

The arc of ascent is an inward journey in which one detaches oneself from material, vegetable, and animal needs and desires to rise through the world of intellects toward God. In this ascent, change occurs not only in the accidents of the person; rather, the substance of the person itself is transformed. This is called “substantial motion” (ḥarakat al-jawhariyah). For Mulla Sadra, this continues after the departure of the soul from the body, when the imagination, freed from corporeal restraints, becomes more powerful in its creative abilities, so that it beholds its own afterlife and bodily resurrection.

The arc of descent mirrors the arc of ascent because the human soul is a microcosm. The levels one discovers within oneself to be related through variations in the intensity or causal grounding within one’s very existence correspond to the levels of intensity of being in the external world. Claims on behalf of this correspondence have been made throughout the history of ancient Greek, Christian, Jewish, and Islamic philosophy. In the historical development of ideas leading from Plato to Mulla Sadra, the place of the imagination is elevated from Plato’s eikasia to the eternal immaterial creative imagination of Mulla Sadra, matching the elevation of the world of imaginal forms from the play of shadows on the wall of Plato’s cave to the mundus imaginalis of Sohravardi. Two innovative features of Mulla Sadra’s transcendental philosophy are motivated by requirements for the maintenance of the correspondence between microcosm and macrocosm: the immateriality of the imagination and the graduated intensity of being.

References

Abedi, Ahmad. "Tashkik dar Falsafeh Islami (Gradation in Islamic Philosophy)."

Faslnameh Pazhuheshha-ye Falsafi - Kalami, no. 5 & 6 (1379/2000): 34-47.

Adamson, Peter. The Arabic Plotinus. London: Bloomsbury, 2003. Avicenna. Al-Mubahathat. Edited by Muhsin Bidarfar. Qom: Bidar, 1992.

—. The Metaphysics of the Healing. Edited by Michael E. Marmura. Provo: Brigham Young University Press, 2005.

Black, Deborah. "Mental Existence in Thomas Aquinas and Avicenna." Medieval Studies 61 (1988): 45-79.

Black, Deborah. "Rational Imagination: Avicenna on the Cogitative Power." In Philosophical Psychology in Arabic Thought and the Latin Aristotelianism of the 13th Century, edited by Luis Xavier López-Farjeat and Jörg Alejandro Tellkamp. Paris: J. Vrin, 2013.

Borqei, Zohreh. Khiyal az nazar-e Ibn Sina va Sadr al-Muta'alihin. Qom: Bustan-e Kitab, 1389/2010.

Chittick, William C. The Self-Disclosure of God. Albany: State University of New York Press, 1998.

Corbin, Henry. Spritiual Body and Celestial Earth. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1977.

Cornford, Francis Macdonald. Plato's Theory of Knowledge. London: Kegan Paul, Trench, Trubner & Co., 1935.

Esots, Janis. "Cosmic Imagination in the Thought of Ibn al-Arabi and al-Suhrawardi." In

East and West: Common Spiritual Values, edited by A. Asadova, 237-248. Istanbul: Insan, 2010.

Fanaei Eshkavari, Mohammad. "Sohravardi and the Question of Knowledge." Ishraq 2 (2011): 131-143.

Inge, William Ralph. The Philosophy of Plotinus. New York: Greenwood Press, 1929.

Javadi Amuli, 'Abdullah. "Knowledge of the Soul as Path." In Soul: A comparative approach, edited by Christian Kanzian and Muhammad Legenhausen, 17-23. Frankfurt: Ontos, 2010.

Kalin, Ibrahim. Knowledge in Later Islamic Philosophy: Mulla Sadra on Existence, Intellect and Intuition. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2010.

Kazemi, Muhammad Khan. Barressi tatbiqi 'alam-e khiyal az didgah-e Ibn Sina, Shaykh Ishraq, va Mulla Sadra (A comparative review of the imaginal world in the views of Avicenna, Shaykh al-Ishraq, and Mulla Sadra). Qom: Al-Mustafa, 1392/2013.

Kukkonen, Taneli. "Faculties in Arabic Philosophy." In The Faculties: A History, edited by Dominik Perler, 66-96. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2015.

Lovejoy, Arthur O. The Great Chain of Being. Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1936.

McGinnis, Jon. Avicenna. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2010.

Misbah Yazdi, Muhammad Taqi. Philosophical Instructions. Translated by Muhammad Legenhausen and 'Azim Sarvdalir. Binghamton: IGCS and Brigham Young University, 1999.

Morewedge, Parviz, ed. Neoplatonism in Islamic Thought. Albany: State University of New York Press, 1992.

Netton, Ian Richard. Allah Transcendent: Studies in the Structure and Semiotics of Islamic Philosophy, Theology and Cosmology. Routledge: London, 1989.

Nikzad, Abbas. "Tashkik dar tashkik dar tashkik-e wujud-e hikmat-e Sadra'i (Doubting the Doubting of the gradation of being of the Sadrean philosophy)." Ma'rifat-e Falsafi 9, no. 1 (1390/2011): 179-190.

Obudiyyat, 'Abd al-Rasul. Nezam-e Hikmat Sadra'i: Tashkik dar Wujud (The System of Sadrean Philosophy: Gradation in Being). Qom: Mo'assesseh Amuzeshi va Pazhuheshi Imam Khomeini, 1383/2004.

Oshshaqi, Husayn. "Tashkik dar "tashkik-e wujud"-e hikmat-e Sadra'i (Doubting the "gradation of being" of the Sadrean philosophy)." Ma'rifat-e Falsafi, 1389/2010: 11-24.

Plato. Republic. Edited by C. D. C. Reeve. Translated by C. D. C. Reeve. Indianapolis: Hackett, 2004.

Rahman, Fazlur. Avicenna's Psychology. Westport: Hyperion, 1981.

—. The Philosophy of Mulla Sadra. Albany: State University of New York Press, 1975. Rizvi, Sajjad H. Mulla Sadra and metaphysics: modulation of being. London and New York: Routledge, 2009.

Scheiter, Krisanna M. "Images, Appearances, and Phantasia in Aristotle." Phronesis 57 (2012): 251-278.

Shields, Christopher. "Supplement to Aristotle's Psychology: Imagination." Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy. 2015.

http://plato.stanford.edu/archives/spr2015/entries/aristotle-psychology/ (accessed October 11, 2015).

Shirazi, Sadr al-Din. Al-Hikmat al-Muta'aliyyah fi al-Asfar al-'Aqliyyah al-Arba'ah, Vol. 8. Beirut: Dar al-Ihiya al-Turath al-'Arabi, 1990.

—. Al-Hikmat al-Muta'aliyyah fi al-Asfar al-'Aqliyyah al-Arba'ah, Vol. 9. Beirut: Dar al- Ihiya al-Turath al-'Arabi, 1990.

—. The Wisdom of the Throne. Translated by James Winston Morris. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1981.

Shiriazi, Sadr al-Din. Spiritual Psychology. Translated by Latimah-Parvin Peerwani. London: ICAS Press, 2008.

Sohravardi, Shihaboddin Yahya. Oeuvres Philosophiques et Mystiques, Tome I. Edited by Henry Corbin. Tehran: Academie Imperiale Iranienne de Philosophie, 1976.

Suhrawardi, Shihab al-Din Yahya. The Book of Radience. Edited by Hossein Ziai. Costa Mesa: Mazda, 1998.

—. The Philosophy of Illumination. Edited by John Walbridge and Hossein Ziai. Provo: Brigham Young University Press, 1999.

Suzanchi, Husayn. "Tarikhche-ye Nazari-ye Tashkik-e Wujud (A short history of the theory of the gradation of being)." Rahnamun 3, no. 11 & 12 (1384/2005): 93-117.

Watson, Gerard. Phantasia in Classical Thought. Galway: Galway University Press, 1988.

Wolfson, Harry Austryn. "The Internal Senses in Latin, Arabic, and Hebrew Philosophic Texts." The Harvard Theological Review 28, no. 2 (1935): 69-133.

- 1. For example: (Rahman, The Philosophy of Mulla Sadra 1975) 37; (Kalin 2010) 96-102. I do not know where the “two wings” metaphor has its origin; it is not in Rahman (or Kalin or Rizvi) but is common in Persian discussions of Mulla Sadra’s ḥikmat al-muta ‘ālliyah. The term “modulation” is from (Rizvi 2009)

28. An examination of the fundamentality of existence is to be found in (Misbah Yazdi 1999) Lessons 26 and 27, 213-230. Ayatullah Misbah also provides a critical introduction to the gradation of existence: (Misbah Yazdi 1999) 236-237; 250-255.

- 2. (Plato 2004) 479d.

- 3. (Plato 2004) 508b-c.

- 4. (Cornford 1935), 319.

- 5. (Watson 1988), 16-19; (Shields 2015).

- 6. For more detailed analysis of Aristotle’s view, see (Scheiter 2012).

- 7. (Watson 1988) 100-103; (Inge 1929) 184.

- 8. For the influence of Plotinus on Islamic philosophy through the so-called Theology of Aristotle, see (Adamson 2003); for further explorations of neo-Platonism in Islamic philosophy see (Morewedge 1992).

- 9. For a chart of the ten intellects and discussion, see (Netton 1989) 162-172.

- 10. See (Black, Mental Existence in Thomas Aquinas and Avicenna 1988), 10. Since there is no place for mental faculties in God, I would guess that when Avicenna refers to wujūd al-ilāhī (divine existence), this is meant in a broad sense to include the entire divine realm, including the intellects.

- 11. (Rahman, Avicenna's Psychology 1981) 33; (McGinnis 2010) 211-212; (Kukkonen 2015) 86-87.

- 12. This is traced in detail through Greek, Latin, Hebrew, Arabic and Syriac in (Wolfson 1935).

- 13. See the illuminating discussion in (Black, Rational Imagination: Avicenna on the Cogitative Power 2013).

- 14. (Kazemi 1392/2013) 159.

- 15. As Black notes (Black, Rational Imagination: Avicenna on the Cogitative Power 2013), there are various components of her analysis that are contested by other experts, and this is no place to weigh the different sides to the argument. However, the compositional aspect of rational thinking must be carried out through this faculty of takhayyul, which, when governed by the intellect, engages in cogitation.

- 16. See the biographical sketch by Walbridge and Ziai in the introduction to (Suhrawardi, The Philosophy of Illumination 1999) XV-XVII.

- 17. (Netton 1989) 260-269.

- 18. (Netton 1989) 267.

- 19. (Corbin 1977) 76-77.

- 20. (Suhrawardi, The Philosophy of Illumination 1999) 136.

- 21. Both in his earliest philosophical essays, and in the Ishrāqī (Suhrawardi, The Book of Radience 1998) 30-33.

- 22. (Suhrawardi, The Philosophy of Illumination 1999) 138.

- 23. (Suhrawardi, The Philosophy of Illumination 1999) 138.

- 24. (Suhrawardi, The Philosophy of Illumination 1999) 137.

- 25. (Suhrawardi, The Philosophy of Illumination 1999) 336-340.

- 26. (Fanaei Eshkavari 2011) 140. Although the imaginal world is first introduced by Sohravardi and is considered by him to be an important realm that the aspirant must traverse, he insists that the true sage must fare beyond the archetypes to God. See (Esots 2010) who also provides a valuable comparison with Ibn al-‘Arabi’s views of the imaginal world.

- 27. (Lovejoy 1936).

- 28. (Suhrawardi, The Philosophy of Illumination 1999) 111-112.

- 29. (Suhrawardi, The Philosophy of Illumination 1999) 112.

- 30. (Avicenna, The Metaphysics of the Healing 2005) 124-128. Avicenna concludes his discussion of priority with the comment: “You have thus learned that, in reality, act is prior to potency and, moreover, that it is prior in terms of nobility and perfection.”

- 31. (Suhrawardi, The Philosophy of Illumination 1999) 62.

- 32. The claim that there are differences in the intensity of being must be distinguished from that claim that there are different degrees in the application of a concept to an instance of it. Aristotle and the Peripatetics claim that being is said of substances in a sense prior to that in which it is applied to accidents, but not because accidents have a less intense being than the substances in which they inhere, but because accidents are only said to exist because of the existence of the substances in which they inhere. See (Avicenna, Al-Mubahathat 1992) 218 for an explicit affirmation of tashkīk in the predication of being.

- 33. (Sohravardi 1976) 333-334.

- 34. A brief review of the reception of the idea is given in (Abedi 1379/2000); a contemporary charge of inconsistency is made against Mulla Sadra’s view of the gradation of being in (Oshshaqi 1389/2010) to which a reply is given in (Nikzad 1390/2011).

- 35. This kind of response to the illuminationists was given by Mir Damad, the teacher of Mulla Sadra. A detailed exposition of the analyses of accidental gradation is given in (Obudiyyat 1383/2004) 135-189.

- 36. The historical development of the doctrine of the gradation of being is presented in more detail and with further developments among the followers of Mulla Sadra in (Suzanchi 1384/2005).

- 37. A rejection of Sohravardi’s view of phantoms and reflections as imaginal substances can also be found in (Misbah Yazdi 1999) 372-375. For a fuller comparison between the views of Sohravardi and Mulla Sadra on the imaginal world, see (Kazemi 1392/2013) 127-132.

- 38. (Shiriazi 2008) 196.

- 39. The immortality of the imagination and the “strange tail” of the soul is apparently first introduced by Ibn al-„Arabi and taken from him by Mulla Sadra. See (Shirazi, Divine Manifestations 2010) 113-114.

- 40. A brief summary comparison between Avicenna’s and Mulla Sadra’s views of the imagination is given in (Borqei 1389/2010) 246-250.

- 41. (Shirazi, The Wisdom of the Throne 1981) 130-131.

- 42. (Shirazi 2008) 403; 426-427; 523.

- 43. (Shirazi, The Wisdom of the Throne 1981) 132.

- 44. (Shirazi, Al-Hikmat al-Muta'aliyyah fi al-Asfar al-'Aqliyyah al-Arba'ah, Vol. 8 1990) 223, my translation. Cf. (Shiriazi 2008) 194.

- 45. (Shiriazi 2008) 440.

- 46. (Shirazi, The Wisdom of the Throne 1981) 178.

- 47. (Shiriazi 2008) 158.

- 48. For a fuller exposition, see (Misbah Yazdi 1999) 274, 410.

- 49. (Javadi Amuli 2010) 22.

- 50. For background, see (Chittick 1998) 233-237.

- 51. (Shirazi, Al-Hikmat al-Muta'aliyyah fi al-Asfar al-'Aqliyyah al-Arba'ah, Vol. 9 1990) 130-131; my translation here is more literal than that of (Shiriazi 2008) 456.